It’s time for the third part of our series dedicated to the women in Peru! After having presented to you, the women of the pre-Columbian time until the Inca Empire in the first part of our series “Peru in the feminine”, then those who took part in the process of the Independence of Peru, in a second article, we make a good in the time with this new episode which presents you 6 portraits of forgotten women of the Peruvian history, from the 19th to the 20th centuries. These women of letters or of field, artists, scientists or historians give us another perspective of the stories of the Spanish chroniclers.

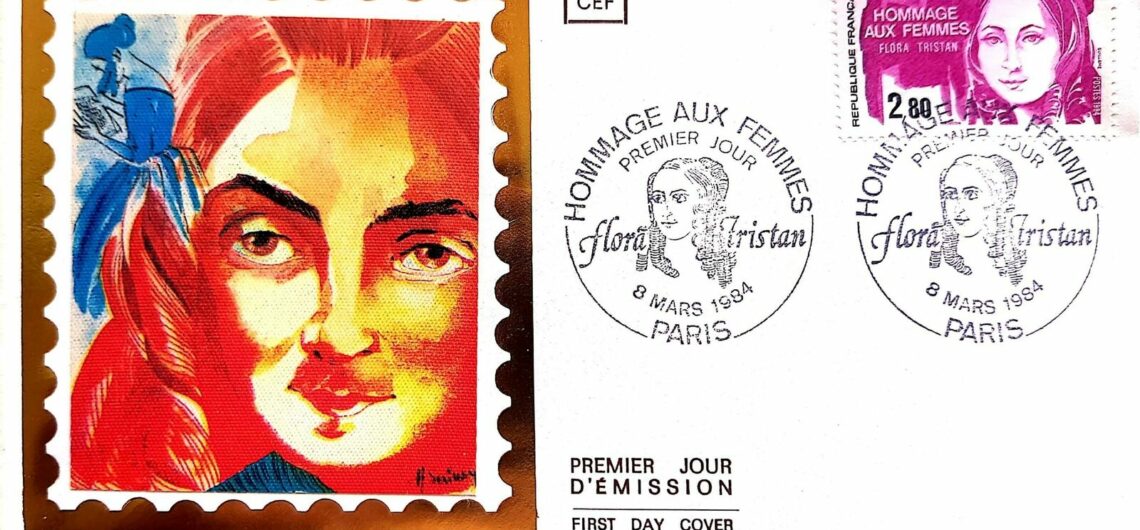

Women of letters and fieldwork: Dominga Gutierrez, Flora Tristan and Francisca Zubiaga

In the 19th century, three women meet by chance in the city of Arequipa, they do not know it yet but they will have a notable impact on the currents of thought of Peru. According to the writer and researcher Sara Beatriz Guardia, director of CEMHAL (Center of Studies of the Woman in Latin America), they are the forgotten ones of the Peruvian history and nevertheless to return on their respective courses show well that they had an impact on the progressive vision of Arequipa until the hour of today.

In order from left to right, portraits of Dominga Gutierrez, Flora Tristan and Francisca Zubiaga

Born in 1803, in Paris, it is a relatively complex family history that will bring Flora Tristan to cross the Atlantic. At first, she traveled for her own personal reasons, but this trip had an impact on the people and situations she met and was to have more than a personal impact. Her father died when she was four years old, leaving her family in financial difficulty. In search of her inheritance, she went to Peru and met her uncle Pio de Tristan y Moscoso, a Peruvian nobleman who gave her a pension for a few years, because she was the natural daughter of his brother. She describes herself as an “outcast”, that is to say a “bastard”, because of her situation. For two years, she lived with this new family and discovered the world of the aristocracy in Arequipa. Marked by her trip to Peru, she writes her book Peregrinations of an outcast (1833-1834) with the eyes of a young Parisian woman with a strongly secular and republican education. She describes the social and political life, the influence of the Church and especially slavery. The book will be perceived as a scandal in Lima and Flora’s uncle will cut her pensions. With a good management, she will be able to live in a decent way with what she had already received.

Flora Tristán lives the hipocresía of the alta sociedad criolla and the civil war between dos gallitos, Agustín Gamarra y Luis de Orbegoso, aunque quien la cautiva es la esposa del primero, Francisca Zubiaga y Bernales, La Mariscala, mujer de armas tomar, literalmente, bregada en primera línea de combate al lado de su marido.

Flora Tristán experiences the hypocrisy of the Creole high society and the civil war between two roosters, Agustín Gamarra and Luis de Orbegoso, although she is held captive by the wife of the former, Francisca Zubiaga y Bernales, La Mariscala, a woman in arms, literally in the front line of the fight alongside her husband.

Source and translation: https://latinta.com.ar/2019/12/peregrinaciones-de-una-paria/

What one will retain of its impact is probably its influence on the big debates notably on the slavery. She will also conclude later that her trip to Peru allowed her to realize and reinforce her feminist activism which was already present in her since her youth. She doesn’t pretend to understand the whole society but she denounces without mincing her words the living conditions of the slaves, in particular the women and denounces these unhealthy practices. Her work – and others that at the time dared to denounce the conditions of the slaves and criticized society in general – was burned in the main square of Arequipa, a sign that the aristocrats did not look favorably on it. On her return to France, she began a campaign for the emancipation of women, the rights of the working class, the right to divorce, the abolition of the death penalty and the easing of restrictive marriage rules. On the European continent, she is considered one of the greatest French activists and feminists, whose struggle is often compared to that of Simone de Beauvoir.

In the same tragic story of Flora Tristan, it is the death of her father that will sign the destiny of the one called the “nun Dominga Gutiérrez”. This story of Dominga Gutiérrez is also interesting for the place it left in the collective memory of women of the time and especially the place of the Church. When she was 5 years old, her father died suddenly and left a trauma to the little girl and to the whole city of Arequipa. Indeed, her father Don Raymundo Gutiérrez de Otero was one of the main actors involved in the insurrection movement against the Spanish crown. Dominga, on the other hand, had a childhood that was caught up in these political movements and popular struggles. At the age of 13, she met a doctor who was ready to marry her, but her mother insisted that she wait a year to get an education at the convent. But the impatient doctor married another woman and left Dominga and her family in disgrace. She was a distraught young woman who accumulated tragic events during her young years that forged a depressive personality. In 1821, she was sent as a novice to the monastery of Santa Teresa in Arequipa, under the direction of the Carmelitas Descalzas. Dominga returned to the convent at the age of 14 and instead of taking her vows as a nun, she had to take her perpetual vows and become a sister with the black veil, that is to say, one who had to remain in the convent and the orders in perpetuity. Suffering from a great depression and loneliness, she asked several times to leave. It is the slow descent into hell that begins, not feeling at home among the nuns, she wishes to return home, but each request ends in failure. Ten years later, in a state of depression and advanced illness, she decides to run away from the convent. This escape, quite theatrical and orchestrated, will mark the spirits: helped by some other sisters, she introduces a corpse in the monastery, creates a fire by burning her face. By causing this fire, they attract the attention of the superiors and take refuge in a room rented beforehand by other nuns. In other words, finding a half-burned corpse in a monastery was enough to create a scandal, which the ecclesiastical body immediately tried to minimize. Dominga was taken in by her uncles Thenaut-Gutiérrez who offered her hospitality in the name of freedom.

Flora Tristan will reveal in her writings that Dominga had been inspired by one of the “forbidden” readings she had done in the monastery to organize the escape. The story could have ended there, but once outside, Dominga does not hesitate to reveal the atrocities made inside the convent: the rigor, the discipline of the monastery, the austere and gloomy atmosphere, the immoral acts of the superior sisters and provokes a real questioning of the place of the Church in the Peruvian society. Debates emerge on the question of the sanctity of religious practices and the great number of women sent to convents and monasteries.

With the passing of time, it is thus the bourgeois and aristocratic circles which are disputed by Flora Tristan, then Dominga reveals to the great day the abuses of powers and authorities of the Church.

There remains only a small questioning of the military institutions to unbalance a society. This leads us to the story of the one called “la Mariscala”. Her full name is Francisca Zubiaga y Bernales, she was born in 1803 in the region of Cusco, she was not really predestined to be a woman of war, but this is how she is described today. Daughter of the countryside, she moves with her family, mainly under the influence of her father who inculcates her a very strict education, however her courage and her determination are going to give her a very different destiny. In the middle of the war of independence, she married General Agustin Gamara, who was victorious in the battle of Ayacucho. She was nicknamed “Doña Pancha” and prepared herself for war by learning to handle weapons and swords, and to ride horses. But what were the motives that pushed Francisca to oppose and get involved in this war at her young age of 25? Dressed in pants, boots and military uniform, she supervises her troops herself.

Considered as the first lady of Peru and especially the first political woman, she implies herself fully in the Peruvian invasion of Bolivia in 1828, to thousand places of the occupations of the women of the time. Her very authoritarian positions created the scandal in the Peruvian society. She also crossed the road of Flora Tristan.

“Like Napoleon, all the power of her beauty was in her look; how fierce, how proud and penetrating; with that irresistible ascendancy she commanded respect, chained the wills, and won admiration” wrote Flora Tristan about Francisca in her book Peregrinations of an Outcast (1833-1834).

“Like Napoleon, all the empire of her beauty was in her look; how fierce, how proud and penetrating; with this irresistible ascendancy, she commanded respect, chained the wills, captivated admiration.”

Through her involvement in this very masculine military environment, she also questioned the place of women in relation to their civic duty, their political positions and their implications in general in society. She ended her life near Valparaiso, Chile, suffering from tuberculosis, at the age of 31.

Although they are forgotten figures of history, they are witnesses of a changing society, and of new ideas that will represent a part of the beginnings of the Independence of Peru. In spite of the censorship, the scandals and the autodafés, their legacies are more important today. Peru becomes independent on July 28, 1821.

From archaeology to music, through research on the Inca empire, what we owe to Maria Reich, Chabuca Granda and María Rostworowski

In the 20th century, these women became famous for their excellence in the scientific and artistic fields. We can mention Maria Reich, María Rostworowski, Chabuca Granda who, despite their great differences, are today notable figures of Peru and have left a mark in the culture, history and heritage of the country.

In order, from left to right, the portraits of Maria Reich, María Rostworowski and Chabuca Granda

Source : https://fr.wikipedia.org/wiki/Chabuca_Granda

More known by her discoveries than by her name, Maria Reich was born in 1903 in Dresden (Germany) but her destiny brought her to the other side of the Atlantic, and more precisely to the region of Nasca. Indeed, she made famous the lines of the same name, which until today remain one of the mysteries of Peru. Although she was not of Peruvian nationality, Maria Reich dedicated all her life to the country and to her research. According to her, the geoglyphs had a function of astronomical calendar in order to observe the cycles for the agriculture. In family rupture and wishing to flee the First World War, it is during her second trip to Peru, in the Andes in 1934 that she decides to settle there. At the time “the Lady of the lines”, as she was nicknamed, was able to discover 18 figures of animals and plants. Today there are more than 150 lines in the area of Nazca and Palpa. Since 1994, the “lines and geoglyphs of Nazca and Palpa” are classified on the list of the world heritage of the UNESCO. Currently, a museum featuring the living conditions of the researcher is located a few kilometers from the Nazca lines. In addition to her work, her personality as well as her integration with the local populations is put forward, she was indeed polyglot and had learned Quechua.

We can also mention Chabuca Granda, famous artist of the 40s in Peru. Although native of the city of Cotabambas, of the region of Apurimac, it is in the bohemian district of Barranco in Lima that – of her real name, Maria Isabel Granda Larco – finds her inspiration. She is both a Peruvian singer and guitarist and performs from a young age in singing competitions. The song “La Flor de la Canela” (1953) is one of the Peruvian classics on an international scale. It is a mixture of waltzes and rhythms of the Pacific coast as the “tondero”, the “marinera limena”. The text is about a mestizo woman whose skin color is “cinnamon”, who lives in Lima, a way for Chabuca Granda to express his nostalgia for the Limenian capital that has undergone great changes. Her emblematic deep voice has become a symbol for the nation. She also participated in the creation of the famous song “El Cóndor Pas” with Daniel Alomía Robles, which is one of the most famous songs of Peru, the anthem of the Andes.

More contemporary, we find María Rostworowski born in Barranco, of a Polish father and a Peruvian mother, she is one of the most famous Peruvian historians. After many trips with her family to Europe, she became one of the greatest historians of the 20th century.

She dedicated a great part of her research to Peruvian history, especially on the Inca Empire, with her first work on Pachacútec Inca Yupanqui and the biography of Francisca Pizarro, the daughter of the Spanish conquistador. Alongside her academic and historical research, she holds a position at the Peruvian Embassy in Spain, as well as a position as director of the National Museum of History. Her writings also contributed to give another perspective to the Old Peru, which was based essentially on a European vision, sometimes far from the local reality, thus to allow Peru to rethink its history, by moving away from the colonialist representation of the accounts of the Spanish chronicles.

This list, not exhaustive, of famous women of Peru show the diversity and the different destinies according to the times, having contributed in a way or another, to the history and the heritage of Peru.

Join us in a few times for the end of this series dedicated to the women of the Peruvian history by plunging back to our time to meet the women of every day of Peru. To know more about the history of Peru and its cultural themes, as well as to realize a trip to Peru, do not hesitate to contact us.

Comments