Choquechaka, Tandapata, Atoqsaykuchi, Teqsecocha, …. here are some of the many names you may have read on the street signs in Cusco during your last stay in the ancient capital of the Inca Empire. “Funny”, “Exotic” or “Unpronounceable”, these names in Quechua may seem complicated, but in reality they represent one of the richest and most captivating cultural legacies of Cusco. In fact, behind its original names lies the former Cusco … and a simple translation is often enough to travel through time and discover the panorama, history and the 1000 stories of the glorious and immemorial streets of the world’s bellybutton.

To do things in order it is important to have some historical data.

In the time of the Incas, town planning went much further than one could imagine. In fact, the organisation of the city first of all responded to human and economic needs. As Inca society was an agricultural society, the best land was reserved for crops and was not to be “wasted” for the construction of temples, for example. Inside the cities, the logic was the same, with always very narrow streets in order to make the most of the space.

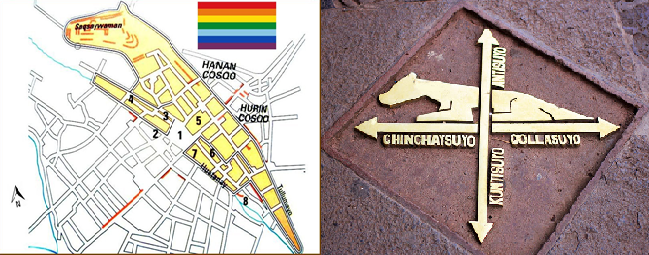

Furthermore, urban planning also integrated concepts of respect and adaptation of cities with their environment. Indeed, society had to associate and incorporate itself with nature and local gods (Pachamama, Apus or Spirits of the Mountains, Wakas or natural temples, …) rather than destroying them to settle in their place. Finally, the urban organisation could include a part of symbolism, as can be seen in the diagrams of the city of Cusco in the shape of a puma, the site of Pisac in the shape of a condor or the ancient citadel of Ollantaytambo in the shape of a llama.

As shown in the picture above, Cusco would therefore have been built in the shape of a Puma, a sacred animal in the Inca’s time. Although some people think that this is actually the result of chance, the names of the streets, sites and neighbourhoods of the time, such as Pumakurko (back of the puma), Pumaqchupan (tail of the puma) or Saqsaywaman (potentially derived from saqsa uma, hard head or marble head) seem to show that this was in fact the result of real reflection and choice on the part of leaders at the time.

Moreover, Cusco responded at the time to a well-defined urban plan integrating the central principles of Bi, Tri and Quadripartite, symmetry, opposition and repetition, while always respecting the religious, economic and ecological elements mentioned above. Thus, the city was divided into two parts (Hanan Qosqo and Urin Qosqo), four sectors (corresponding to the 4 “suyos”: Chinchaysuyo, Collasuyo, Contisuyo and Antisuyo) and 12 or 13 districts according to the authors. For Garcilaso Inca de la Vega, the imperial city included the sectors of Qolqanpata, Kantupata, Pumakurko, T’oqokachi, Munay Senqa, Rimaq Pampa, Pumaq Chupan, K’ayao Cachi, Ch’akill Chaka, Piqchu, Karmenqa, Wakapunku, K’illipata and Pumakurko while Manuel Chavez Ballon for his part removes the two last one to add the Qoripata district.

If the versions are differents concerning the number of districts, all the studies confirm that the life of the Inca capital was already concentrated around the main square before the arrival of the Spanish. According to different writings, this square was surrounded by the great imperial palaces and divided into two parts (Wakaypata for ceremonies / Cusipata for festivities) by the Saphi River.

If the translation of the names of the Quechua routes shows that they were very much related to the intrinsic aspects of the streets and the events taking place there, the arrival of the Spanish marked an enormous upset in the urban organisation and particularly in the naming of the city’s streets.

The different Inca neighbourhoods disappeared in favour of the Spanish parishes and the Quechua denominations gave way to the names of the saints. T’oqokachi thus became San Blas, Karmenqa became Santa Ana, Ch’akill Chaka became Belen/Santiago, …

Apart from the religious aspect, certain districts, avenues or places are renamed according to the craftsmen developing their activity there or the personalities living there. These include the streets Heladeros (street of the ice-cream sellers), Plateros (street of the goldsmiths), Espaderos (street of the swordsmen), Montero (name of the owner of several buildings in the alley), Del Marques (name derived from the Marquis of Valleumbroso) or the “portals” of Panes, Carnes and Harina in the Main Square (names associated with the products sold there during the colonial period : bread, meat, flour).

Time passed and this process of Hispanicisation or transformation of names has become more pronounced. Nevertheless, to our great delight, some of the alleys have been able to stand the test of time and have preserved their Quechua name. Forgotten by Spaniards, little frequented or with a name that is deeply rooted in oral tradition, there are many reasons why their Quechua identity has been preserved over the years.

These streets (“calles” in Spanish) are now an integral part of Cusco’s city centre and represent a cultural treasure that allows us to travel 500 years back in time and imagine the world’s bellybutton as it was known by the illustrious Pachacutec, Inca Roca and Atahualpa.

Let’s discover today these magnificent streets where everyone is walking every day without having the slightest idea of the exceptional heritage they represent …

1) Calle Kiskapata

As with various places in Cusco, Kiskapata includes the word “pata”. Before going into detail it seems important to define this suffix which will be found many times in our article. Translated from Quechua, “pata” means square, place, platform, terrace, edge, step or the upper part of something. It is therefore not surprising to find it in every expression related to a concept of location or space.

Located in the San Blas district, the Calle Kiskapata is a long street linking Jardines del Inca and Tandapata streets, passing through the famous Mirador of San Blas. In English its name could be translated as “thorny place”. Although today the street is clear, at that time there were many shrubs with saw-shaped thorns piercing the leather of the shoes and being extremely painful and prickly, hence its name: Kiskapata, the place where you can find thorns.

2) Calle K’aqlachapata

Even though we have not lived in the time of the Incas, it is possible to say that this street was for a long time a place without vegetation.

Indeed if we translate the word K’aqlachapata from Quechua it means “place of sheep’s leather from which all the wool has been cut”. This name is probably due to the fact that at that time the street was probably only covered with very few grasses and for this reason the inhabitants had to compare it to the sheared skin of a sheep.

3) Calle Qanchipata

Also located in the district of San Blas, Qanchipata takes its name from “Qanchis”: number 7 in Quechua and “Pata”: place, terrace, coast, stairs, … as mentioned before.

This street was given this name by the former neighbours of the parish of San Blas. Already counting 6 slopes in the neighbourhood, the street was the 7th, hence its name: “The 7th slope”.

4) Calle Hatun Rumiyoc

Located between the San Blas district and the main square, Hatun Rumiyoc Street is now one of the most visited streets in Cusco. It is bordered by the ruins of the Inca Roca palace (now property of the Archbishop of Cusco’s palace, where the Museum of Religious Art is located), and is home to one of the most important symbols of Inca culture and architecture: the stone of the 12 corners, the keystone of the facade on which all the other blocks fit together perfectly.

Used by many companies in the region for their visual identities, the wall on Hatun Rumiyoc Street is surely the most beautiful representation of Inca genius and talent in construction. Made up of huge blocks offering a unique decor, the walls of the street will have earned its name from the Quechua words “Hatun”: big, enormous, imposing, majestic and “Rumi”: stone … simply and logically the street with big stones.

5) Limacpampa

Having been distorted, the original name of the square was Rimacpampa. Deriving from “Rimac” meaning the voice, the word, the speaker, and from “Pampa” referring to the place, the esplanade or the square, Limacpampa would therefore be “the square that speaks”. But why is that?

Today made up of 2 parts (Limacpampa Grande / Limacpampa Chico), the square was at the time a space where the population was brought to meet at the sound of the “pututu” in order to learn about the provisions concerning the cult of the sun. It was therefore not “the esplanade that spoke” as its name might indicate, but rather “the square where the Inca high priests of the Qoricancha came to speak to the population” in order to announce the ceremonies in homage to the Sun.

6) Calle K’illi (Calle Heladeros)

Located on the edge of Plaza Regocijo, the Calle Heladeros takes its name from the colonial period, when the two Romani sons installed two ice cream factories there. These two renowned establishments earned it its reputation as “Heladeros Street” or “The Ice-cream sellers Street” in English .

However, if we go back a little further, we can note that this street was not always known as such. In fact, in many chronicles, Calle Heladeros is referred to as Calle “K’illi”. In Quechua, this term refers to birds, especially the “cernicalos americanos”, a species known in Quechua as the Kestrel. There is no doubt that many of them must have been on the roofs of the houses at the time and for this reason the inhabitants could have decided to baptise the place as “the street of the Kestrels”.

7) Calle Choqechaka

Located between the San Blas district and Nazarenas Square, Choqechaka Street can be translated as the Golden Bridge in English (Choqe: Gold / Chaka: Bridge). Where does this name come from?

Once crossed by the Tullumayu river, Choqechaka street was mainly known in the past by the presence of various bridges linking the centre of the city with T’oqokachi, the current parish of San Blas. If today San Blas is famous for its craftsmen and for its bohemian atmosphere, things were quite different back then. In fact, according to oral tradition and popular mythology, T’oqokachi was the area where the Incas hid their jewels, hence the idea of the golden bridge leading the population from the central square to the treasures of the empire.

8) Calle Saphi

Today paved, Saphi Street was in the time of the Incas a river that crossed and divided the main square of the city into two spaces mentioned in the introduction of this article: Cusipata and Waqaypata.

If nowadays Saphi Street is only one street among many others, its importance at the time must have been much more pronounced. Indeed in Quechua “Saphi” means “Root”. A translation which leads us to believe that the Saphi River, which later became Saphi Street, was at the origin of the urban development of the former imperial capital … And that it was probably from this street that the other roads and boulevards of Qosqo began to spread out.

9) Calle Tullumayo

Located in the extension of Choqechaka Street, Tullumayu Street takes its name from the river of the same name which ran through it in the time of the Incas. Translated from Quechua “Tullumayu” can have two translations. While “Mayu” means the river, “Tullu” can designate according to the concept bones or something thin, fragile, weak.

By transcription, “Tullumayu” street would therefore be the street of the “river of bones” or the “weak river”. Perhaps at that time the slope’s inclination generated eddies and therefore a whitish water colour leading the population to compare the canal to a river of bones.

The other explanation, more logical and plausible, would rather be due to the presence at the time of two rivers in the city of Cusco. One very important that we have just mentioned (the Saphi River) and the other, which is more outlying, has less flow and is therefore considered smaller, weaker: the Tullumayu River.

10) Calle Teqsecocha

Connected to the Main Square by Procuradores Street, Teqsecocha Street is surely the street whose name still leaves the most doubts and uncertainties. In fact, if one translates “Teqsecocha”, it could come from “T’aqsay” meaning to clean, to wash something and from “Qocha” relating to water, to the lagoons.

When the street is now paved and shows no trace of an ancient body of water, why would it have inherited the name of “lagoon where one cleans”?

Did the proximity of the Saphi River generate overflows and floods in the area at the time? Or was there a fountain in the street in honour of the Mama Qocha where people came to “clean” or perhaps more accurately to purify themselves?

11) Calle Pumaphaqcha

During the colonial era a large part of the area belonged to Cristobal Sotelo, but during the incanato this street was a place of ceremony and veneration. There was a fountain in the shape of a puma (sacred animal for the Incas), which the Incas worshipped and purified themselves in it. It is precisely from there that the name Pumaphaqha, the “fountain of the puma” in English, is derived.

12) Calle Bancopata

Today known as Calle Bancopata, the street takes its name from the Quechua words “Wanqo”: deaf and “Pata”: the place, the square, the slope.

Located near the ovalo Pachacutec, the street is never visited by tourists today because of its distance from the historic centre of Cusco. However, during the colonial period, the area played an important role in the daily life of the population. In fact, Wanqopata was the location of the Inquisition’s jail. Oral tradition tells that when the prisoners asked for forgiveness and mercy, they were never heard by their executioners … hence the name of the street: “the place of the deaf”.

13) Cuesta Sikitakana (Calle Resbolosa)

Nowadays called “calle Resbalosa” (slippery street in English), the coast leading from Waynapata (defined below) to the church of San Cristobal had a name a thousand times more comical before the arrival of the Spaniards. In fact, at the time of the Incanato the place was known as the cuesta “Sikitakana”. If the idea is the same, that is to say that the street is smooth and uncertain, the Quechua expression seems to us much more poetic !

While “Siki” means buttocks or anything related to the butt in general, “Takana” is used to define the action of hammering or hitting with an object. Rather than the “slippery street”, the Incas had therefore named the place as “the slope that hammers your bum”.

The image is much more meaningful, isn’t it?

14) Calle Chiwanpata

Leading to the market of San Blas, Chiwanpata street takes its name from a beautiful red or yellow bell-shaped flower that grew in abundance there in the Inca period. Known as “Chihuanhuay”, this attractive flower used for ornamental and decorative purposes inspired the name of the street which, if we are to be completely accurate, should logically have been called Chihuanhuaypata in the past.

15) Calle K’urkurpata

Located in the San Blas district, K’urkurpata is also one of the streets whose panorama and vegetation of yesteryear can be imagined by a simple translation. In fact, the “k’urkur” is a plant that can be compared to bamboo, whose straight and consistent stems were used for the construction of roofs. Without having lived during the Inca period, we can nevertheless affirm that the area was certainly used as an area for the extraction and production of this plant for the construction needs of the city.

16) Calle Waynapata

Located between the Main Square and the church of San Cristobal, the street of “Waynapata” derives from “Wayna”: youth and “Pata”: the place, the spot, the square.

The place for young people? Would this mean that the Incas already had a party district where the new generations came to dance to the sound of the “pututu” and drink the “chicha de jora”?

Not at all …

At the time of the incanato the street was occupied by all the military schools of the empire where the young shoots came to be educated, hence its name.

17) Calle Q’era

Now more popular rather than touristic, Calle Q’era is frequented daily by hundreds of people going to the “El Carmen shopping centre”, which specialises in electronics. At the time of the Incaico Empire, things were very different. The word “q’era” was used to refer to a wild grass that is known today as wild lupine. The population used to come here to harvest it to prepare the delicious tarwi.

A street of lupins that became a computer street, as a symbol to show how times are changing.

18) CollaCalle

Located in the extension of Pumapaqcha Street between Limaqpampa Square and San Blas Market, Collacalle takes its name from the 4 regions of the Inca Empire. In the introduction we mentioned that Cusco was divided into 4 sectors corresponding to the 4 regions of the empire: Chinchaysuyo, Collasuyo, Contisuyo and Antisuyo.

The name of the street is directly inspired from Collasuyo. Why is this?

According to oral tradition, it was through this street that the representatives of Collasuyo arrived and also in this street that they were accommodated when they came to Cusco to take part in the different celebrations held in the imperial city.

19) Calle Amaru Ccata (Siete culebras)

Located between Choqechaka Street and Plaza Nazarenas, Calle Siete Culebras offers a unique setting where many tourists and professional photographers like to use their cameras. Between white walls and Inca walls, it is true that this narrow passage presents a captivating and singular atmosphere that invites to take picture and/or a break according to one’s preferences.

Although the setting is splendid, it is another element of the street that often attracts the attention: its name. Indeed, why is this passage called “the alley with 7 snakes”?

Although the name has evolved over time, the meaning and name given to this alley has always remained the same. In the Inca period the street was called “Amaru Ccata”, an expression made up of “Amaru” meaning snake and “Qata” applying to the coat or blanket.

“The street with 7 snakes” in Spanish, “the passage covered with snakes” in Quechua. On reading these names the place suddenly becomes much less hospitable. However, if you think about it, it seems imposible that a whole street has been covered with snakes for years without anyone finding it abnormal, isn’t it?

In fact, to understand the name of this street you have to look at its walls and especially at the old Casa de las Sirenas (now known as the Palacio Nazaneras). In fact, there are 14 snakes carved into its façades, 7 of which are on the wall forming part of Amaru Ccata.

20) Cuesta Atoqsaykuchi

Connecting Choqechaka Street to the upper part of Tandapata, the Atoqsaykuchi Slope is a very long steep street running through a large part of the San Blas district. In Quechua “atoc” refers to the fox, while “sayk’uchiy” means to tire. According to the literal translation, this street would be “the coast that tires the fox”. So where does this name, as cute as it is original, come from?

According to oral tradition, for many years the end of the street had a large quadrangular stone carved in relief on which figures of foxes running and sticking out their tongues could be seen, as if to symbolise the tiredness generated by the long steep slope of the alley. When the urban layout of San Blas was modified, the stone was removed, but its memory has never disappeared from the memories of the neighbourhood. This is still evident today, as the name of the street has not changed … nor has the steepness of the slope …

Although we could go on with this article for another 10 pages, we decided to stop in 20 streets from the ancient Inca capital.

If these few minutes of reading have aroused your curiosity and you would like to know more about the bellybutton of the world, we invite you to also discover our publication on one of the other mysteries of Cusco: The 7 streets in 7 of the imperial capital.

Furthermore, as you can imagine, we will be pleased to guide you and to teach you a little more about the exceptional historical and cultural heritage of Cusco during your stay in Peru. Please do not hesitate to contact us when planning your trip or arriving in Latin America: info@pasionandina.com / Whatsapp: +51 950 307 395 / +51 973 100 626

And for those who have not planned to set foot in country of llamas soon, no problem, write us your questions in commentary of this article and we will be pleased to answer you as soon as possible ?.

Sources :

http://kokocusco.blogspot.com/2016/11/antigua-canalizacion-inca-del-rio.html

http://cuzcomanta.blogspot.com/2008/05/calles-del-cusco-antiguo.html

http://www.qosqo.com/qosqoes/planificacion.html

https://aulex.org/qu-es/

http://www.runasimi.org/cgi-bin/dict.cgi?LANG=es

Comments